Buffer Cache

This chapter describes the buffer cache and how it is integrated with the memory management system as well as the file systems.

15. Buffer Cache#

On a typical paged virtual memory system a very small number of page frames are actually in use at any one time. All memory allocated to a program running in a process virtual address space is virtual memory. When a program starts running none of the virtual pages map to physical page frames until the program references a virtual page without a mapping and a page fault occurs. This happens repeatedly until the program maps an active subset of its virtual address space known as its process working set. Over time all of the running programs create their own process working sets and collectively all processes create a system wide working set which is typically much smaller the all of the page frames on the entire system leaving a set of unused or free page frames. Rather than allowing these free page frames to be unused the memory management system implements a Buffer Cache. The Buffer Cache uses the free page frames as an in-memory cache of file system data and even meta-data.

Each time a file system read occurs the Buffer Cache is searched to see if it can locate an in-memory copy of that data in one of the unused page frames. If that data is found(AKA buffer cache hit) it is simply copied from the page frame to the user buffer. If that data is not found(AKA buffer cache miss) the Buffer Cache allows the underlying file system to read the actual file data into a free page frame before copying it to the user buffer, afterwards any subsequent read for that data will be found in a free page frame(hit). A file system write is similar to a read with the exception that the user buffer data is copied from the user buffer to one of the free page frames and marking that buffer cache managed page “dirty”. The underlying file system is called at some later time to write the contents of the associated dirty free page frame to the file itself and marking it “clean” after. This concept of delaying the writing of modified data from the Buffer Cache to the actual file system is known as a “write-back cache”. This is in contrast with a “write-through cache” which would immediately write the modifications to the file system, blocking the write system call until its complete.

While it does add complexity to the memory management system the technique that the Buffer Cache uses of borrowing free page frames to cache file system data, copying between free page frames and user buffers and delaying the writes results in the file system read and write system calls being thousands or even millions times faster than doing actual file system IO operations. The complexity involves keeping track of which buffer cache pages are dirty and making sure they get written back to the underlying file at some point. How frequently dirty buffer cache pages get written to the actual file is a trade-off. If they are not written back frequently enough the in-memory copy is more up to date than the copy in the actual file. If a system crashes with a lot of dirty buffer cache pages a lot of data in the underlying files will be incorrect and file system data will be lost. On the other hand if the dirty buffer cache pages are written back to disk too frequently(frequency) or too many pages are written at the same time(magnitude), the file data will be written multiple times and the overall system performance will suffer. This is especially true if those files are temporary and will be deleted any time soon as is typically the case when compiling and linking large programs.

In the Unix/Linux operating system the buffer cache is implemented with an array of hash buckets or pointers to the linked list of pages with the same hash. Pages that cache a file’s data blocks are placed in the hash list based on the inode/offset tuple. Once they are on a given hash list they can be easily found by using the inode/offset tuple to generate the hash index which locates the page list to search.

Fig. 15.1 Buffer Cache Structure#

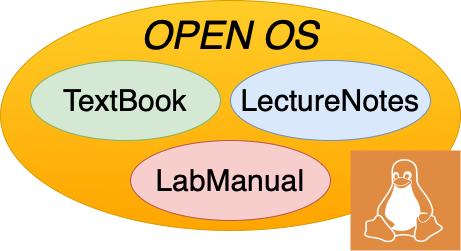

When a file system read() occurs the underlying file system searches the buffer cache for an in-memory cached copy of the file system data based on the inode/tuple for that data. If that data is not found the buffer cache code allocates one or more pages, performs file system read operations for that data along with other surrounding pages and inserts them into the appropriate buffer cache hash list.

Fig. 15.2 Buffer Cache read() with read-ahead#

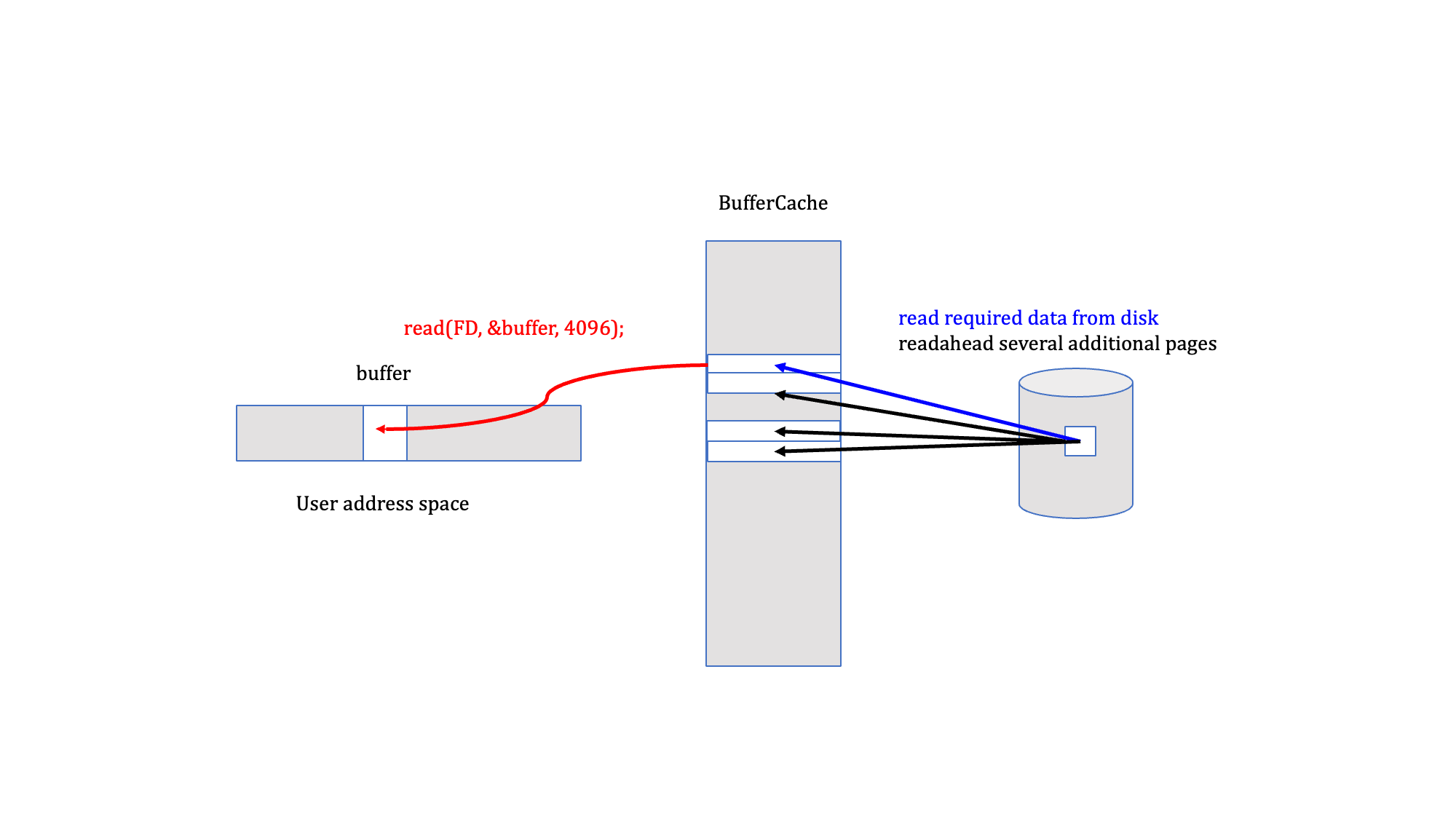

Since more than just the target page is read into the buffer cache subsequent pages are likely found and the read is a simple copy from the buffer cache page to the user’s buffer.

Fig. 15.3 Buffer Cache read() of another page#

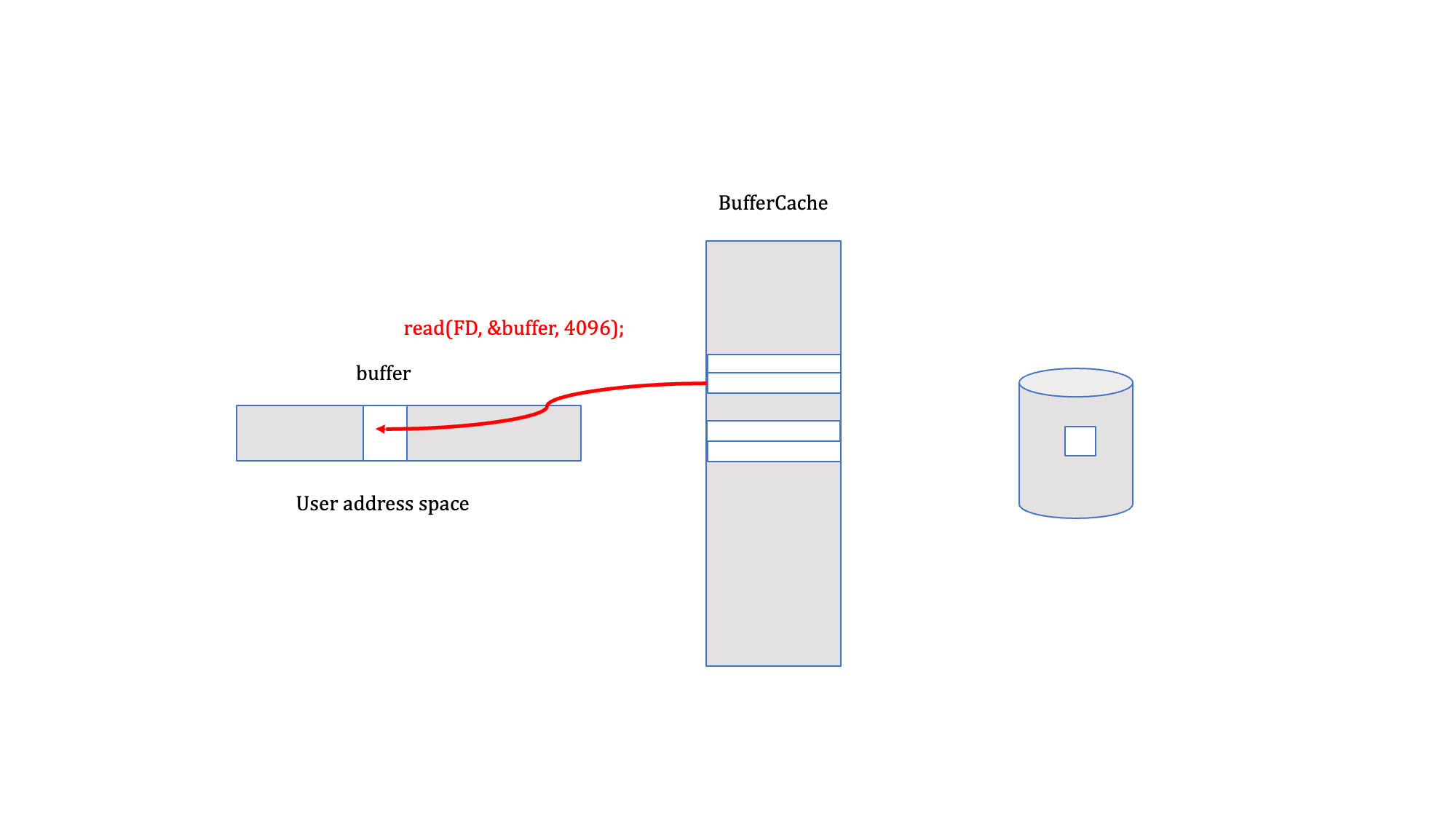

File system write() operations also search the buffer cache for an in-memory cached copy of the file data. If its not found(miss) it must be read into a new buffer cache page inserted into the appropriate hash list so subsequent look up operations will find it(hit). Once the page is found the user buffer is simply copied into the buffer cache page and a modified flag is set for that page. At later time a buffer cache kernel thread or daemon writes that page to the underlying file system and clears the modified flag.

Fig. 15.4 Buffer Cache write()#

Since both the frequency and magnitude of writing/flushing dirty buffer cache pages is critical to both file system correctness and system performance there are often multiple tuning parameters that control this. The frequency which is the time between periodic flush operations is controlled by one parameter and the magnitude which is the actual amount of buffer cache data that is written back to the underlying file system is controlled by another parameter.

The mmap()ing of files also uses the buffer cache pages. The appropriate page table entries that map the underlying file into the processes virtual address space are created with the page frame number(PFN) of the page cache page when the file-backed page fault occurs.

Fig. 15.5 Buffer Cache mmap()’d file#

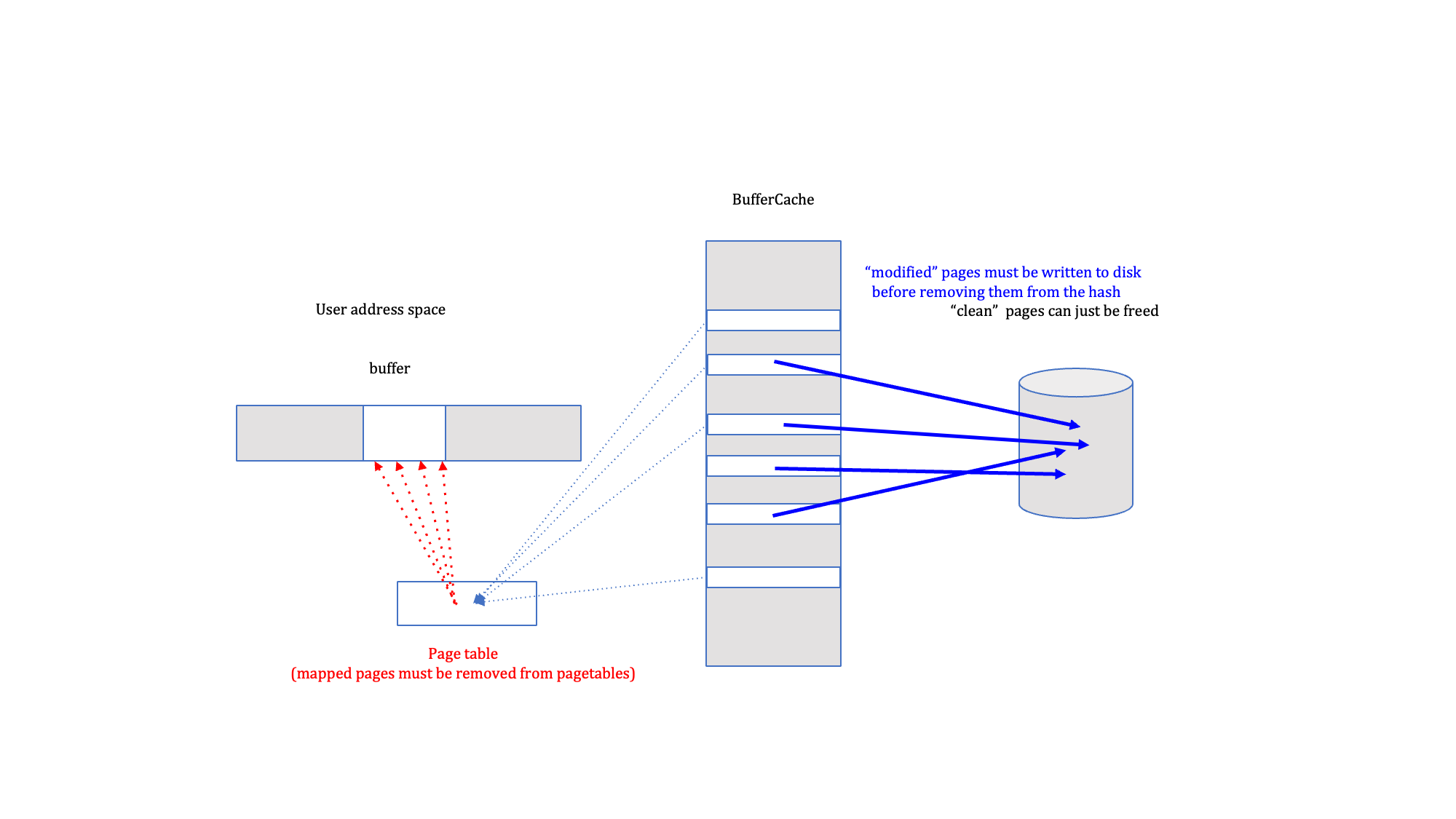

Reclaiming buffer cache pages is typically very simple. Most of the buffer cache pages are 1.) clean/exactly the same as the underlying file system copy in storage, 2.) from a previously closed file and 3.) not mapped into any virtual address. If they are dirty/modified they must be written to the underlying file system and if they are mapped into a virtual address the associated page table entry(PTE) must be cleared out.

Fig. 15.6 Reclaiming Buffer Cache pages#