Purpose of operating systems

Contents

2. Purpose of operating systems#

The purpose of an operating system is to provide everything needed to enable applications to run on computers. We first present a simple model of hardware and why the OS is needed, then discuss how operating systems are the fundamental platform that all computing depends on. We then discuss why developing a fundamental understanding of operating systems is important and how now is such an exciting time to be doing research or development in operating systems.

We understand that studying operating systems is hard. Our hope is that at the end of this chapter you will realize why this course is so important for you as a computer scientist or engineer. Also, we hope a few of you will get excited about the area and consider joining our community of OS developers and researchers. Consider that today’s dominant operating systems are open source and rely on 1000s of contributors from all over the world, many of whom volunteer their time.

2.1. A simple model of hardware#

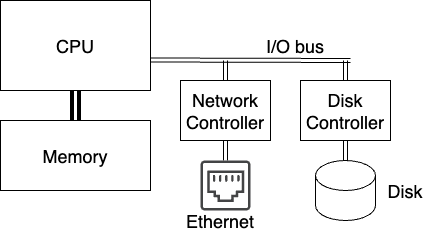

The fundamental job of the operating system is to enable applications to run on a computer. To understand why this is complicated, consider the very simple model of a computer depicted in Fig. 2.1. We briefly describe each of the key components of this computer, and what you need to know for now.

Fig. 2.1 A simple model of a computer. The CPU is connected to high speed memory, and through a lower speed bus to a network controller and disk controller that are in turn connected to a network (ethernet in this case) and a disk.#

Central Processing Unit (CPU): The smart part that executes instructions is called the Central Processing Unit (CPU) or processor. In our simple model, these instructions operate by modifying the contents of various processor registers, loading new register contents from memory, or storing register contents into memory.

Memory: Also referred to as Random Access Memory (RAM), holds the instructions and data that applications require as they execute. It is physically connected to the CPU via direct wiring. Random access here refers to the fact that the processor can directly load or store any memory location (addressed as an 8-bit byte) in the same amount of time. Memory today is normally volatile, meaning that its contents are lost when the computer is powered off.

I/O bus: If the CPU wasn’t connected to anything but RAM, you couldn’t do much with it. All computers have some form of Input/Output (or I/O) bus that connects the CPU and RAM to different devices. While there are many kinds of I/O devices, for now we will ignore everything but: 1) storage, and 2) networks. The processor typically talks to an I/O device by loading and storing registers on a controller specific to the device, and that controller in turn communicates with the corresponding device(s) and transfers data between the device and memory.

Storage: Since the memory is typically volatile, computers have to have some form of storage that is non-volatile or persistent. This may include hard disk drives (HDDs), solid state drives (SSDs), optical drives, usb sticks, etc. Most storage devices are accessed at a block granularity (e.g., 512 or 4096 bytes), meaning that entire blocks are transferred between storage and memory. Most storage devices are not Random Access, for example, technologies like a hard disk drive require the disk head to physically move to the storage location on the disk before reading or writing the data. When the processor wants to read or write a block of disk, it tells the storage controller the block of disk to transfer to or from memory, and the storage controller notifies the processor when the operation is complete.

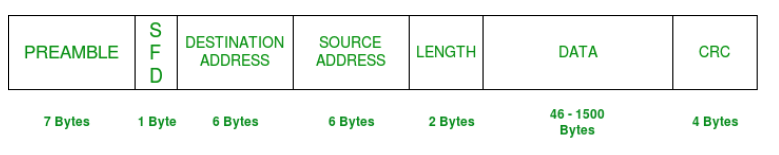

Networking: To talk to the outside world computers are normally connected to some network, typically ethernet today, where data is transferred between memory and the network in some form of packet as shown in Fig. 2.2. When the processor wants to send a message over the network, it first prepares a packet in memory, and then tells the network controller to send it. When new packets arrive over the network, the controller copies them into memory, and then tells the processor (in some fashion) that a new packet is available to be processed.

Fig. 2.2 A ethernet packet is organized into a frame, which includes the destination of the frame, the address of the sender, the length of the entire frame, the data or payload, and a 32-bit hash (the CRC) of the rest of the contents that can be used to check if the packet has been corrupted in transit.#

Note

Note this model is highly abstracted and very simple. As we will learn later in the course:

modern processors can execute hundreds of instructions in parallel, and modern computers can be composed of many processors;

memory today is organized in Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA) where some memory is closer to some processors; so it is not really random access;

memory today is very slow compared to the processor, and normally there are multiple layers of cache so that the CPU doesn’t have to wait for the slow memory every time it needs to fetch an instruction to execute;

and other examples that may arise.

2.2. The fundamental platform#

What makes operating systems so interesting is that they are the fundamental platform on which all other software is written. We briefly discuss each of their core tasks.

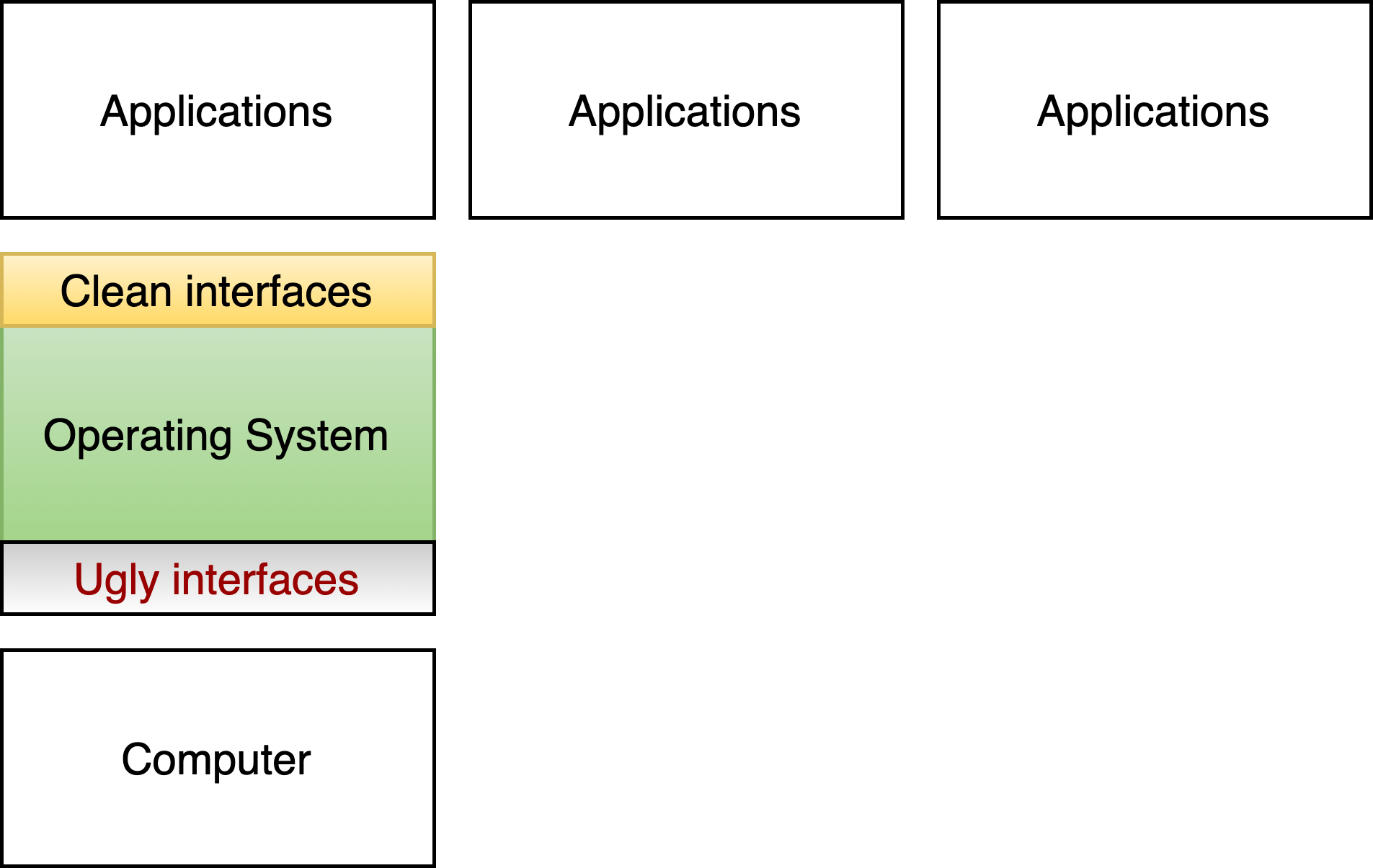

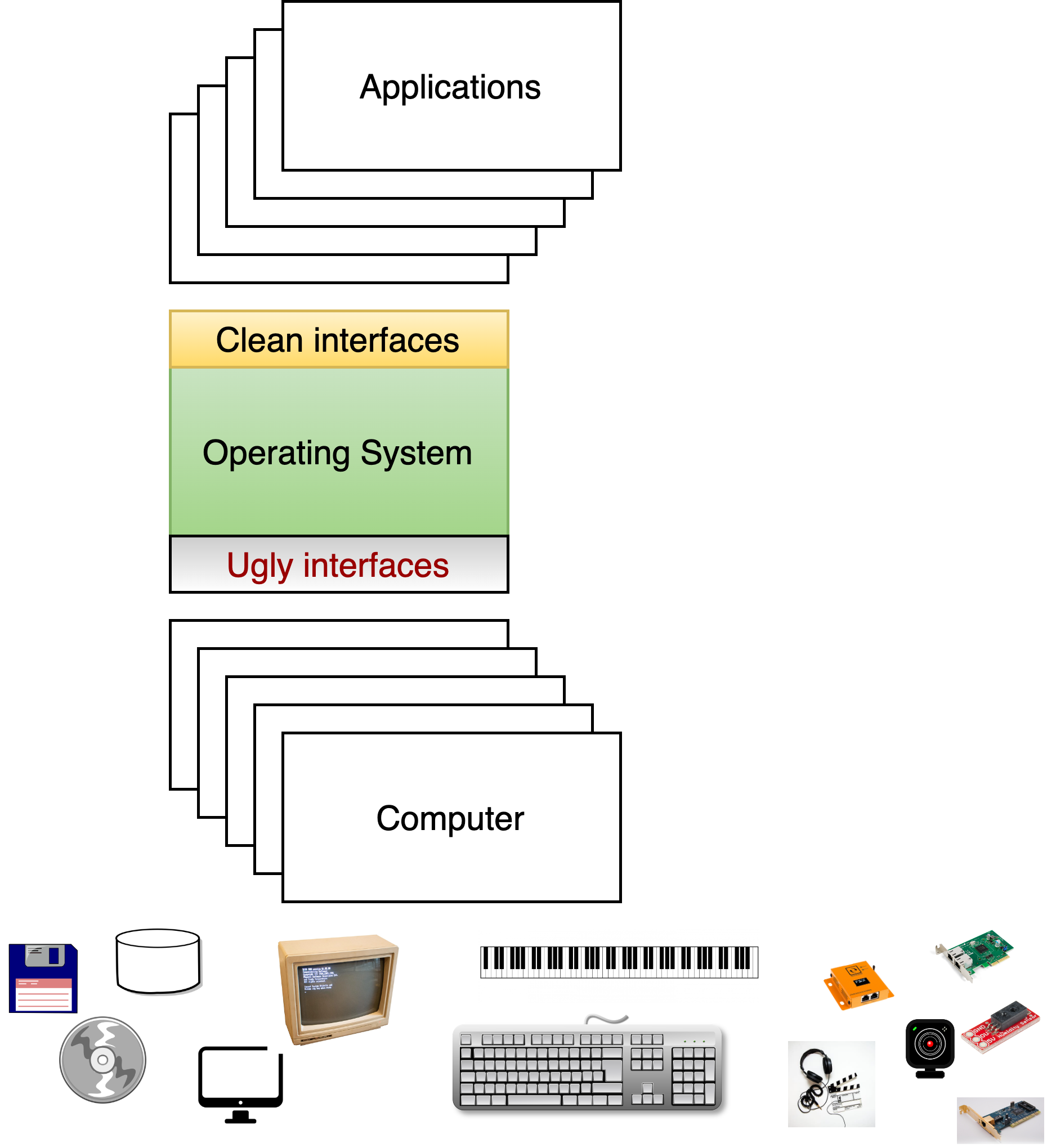

Fig. 2.3 Providing interfaces that applications can use on top of the complicated interfaces of today’s hardware.#

2.2.1. Abstracting Hardware#

If applications needed to understand all the complicated hardware described above, many fewer applications would be written. Consider, for example, storage: the abstraction provided by the hardware is disk blocks, while applications that persist data want to work with higher-level abstractions like directories and files.

As shown in Fig. 2.3, the most important job of the operating system is to enable a set of higher level abstractions, often called “virtual abstractions” on top of the low-level primitive “physical abstractions” provided by the hardware. That is, the operating system translates physical abstractions to virtual/clean ones that applications can be written to. Key virtual abstractions we will discuss include:

Process: An abstraction of computer, where every time a program is started it executes as a separate process.

Files: An abstraction of I/O, enabling processes to persist data in non-volatile storage and communicate with different processes.

Virtual memory: An abstraction of the memory that a process can access.

bash.run("ps -e")

Process versus Program

It is important to understand the difference between programs and processes. When a user wants to run an application, or program, the operating system creates a new process and loads the program instructions from storage into memory for the process to execute. There can be multiple processes executing the same program that are running at the same time. For example, while I am writing this book, when I type “ps -e” to tell me all the processes currently running, (see margin) I find that I have multiple “bash” shells running at the same time, a large number of “python” programs, and of course the “ps” program itself. We will describe this Unix command more later.

Fig. 2.4 Different kinds of computers#

2.2.2. Enabling diverse hardware#

Operating systems must support diverse computer systems (Fig. 2.4), ranging from tiny embedded systems in a smart fridge to massive high-performance computing systems that occupy large portions of a data center. Systems differ in the type of processors (e.g. x86, Power, ARM, RISC6), the devices, and the scale of resources like processors, memory and storage. For example, a smart watch may have just 64 kilobytes of memory whereas a set of new servers just obtained by the Mass Open Cloud have four terabytes of memory, where a terabyte is 1,073,741,824 kilobytes (\(2^{40}\)).

Operating systems provide the same (or similar) virtual abstractions across these very different systems, enabling many of their differences to be hidden from most applications. This makes it easy to write libraries and applications (e.g., Netflix) that can run on systems as diverse as PCs, phones, ipads, and smart cars. This, in turn, makes it possible for hardware designers to innovate, introducing new computers and even processors, while knowing that many applications will be able to use their systems.

In fact, today, the same open source Linux OS runs on cell phones, massive High Performance Computing systems, and drones delivering Amazon packages. As we will discuss, the open source nature of the system enables companies that want to innovate to make changes to the operating system to support their hardware.

While the OS enables applications to be easily ported from one hardware platform to another, the OS is also responsible for meeting the fundamental requirements of the systems it supports. In a cell phone, the OS needs to ensure that everything works in a tiny amount of memory, with limited energy use, while the OS for a server may use terabytes of memory to cache storage and allow many programs to be resident simultaneously. In a drone, one probably wants to make sure that a non-critical program can’t impact the hard real-time programs controlling the propellers.

2.2.4. Supporting many users#

Fig. 2.6 Multiple users#

Normally, operating systems are designed to support different users running processes at the same time. The OS must make sure that one user can’t run processes that change, or even read, the files of another user. Moreover, the OS may need to make sure that each user gets their fair share of the computer; for example, ensuring that a student can’t launch 1000 processes after they are done an assignment to keep classmates from successfully submitting theirs.

This protection is part of the security policies and mechanisms of the operating system. Attacks may try to violate confidentiality (one can see another user’s information), integrity (one can change state of another user), or availability (one can deny other users the ability to run their programs). While OS developers have put enormous work into designing secure systems, the complexity of modern systems give operating system researchers strong job security.

2.2.5. Protecting from external attacks#

The best way to keep users from attacking each other is to make sure that they can’t run on the same computer. In fact, in the good old days, we used to make sure that computers were disconnected from each other. For example, professors had their accounts on computers that students had no access to.

Fig. 2.7 Protecting users from outside world.#

Today we do all our work connected to the network, and we log into our machines remotely. In fact, right now I am typing this sentence on a laptop that is connected to a network; every key stroke I type is being sent over a network to a cloud service running containers reserved by me on a computer in a datacenter 100 miles away from my laptop. The operating system implements firewalls and security policies that make sure that only I can change this book.

While we work hard to protect computers from external attacks, new attacks are always being developed, there are always bugs in the operating system, and humans often expose passwords or make mistakes that render the computers they work on open to attacks. The OS is responsible for logging all the information needed so that we can later figure out who hacked the system, and what changes they made.

Fig. 2.8 Enabling management.#

2.2.6. Management#

There is a huge diversity of systems, from embedded devices to personal computers, cloud data centers, and HPC environments. If a human being was responsible for manually configuring, upgrading, and patching all these systems (which used to be the case), we wouldn’t have enough people in the world.

The tools and capabilities provided in the OS give the mechanism for administrators to automate these activities at massive scale. These mechanisms also allow the operating system to be customized and even specialized to the workload it is expected to run.

Fig. 2.9 Supporting devices#

2.2.7. Supporting devices#

Last, but certainly not least, the OS not only directly manages the hardware of a computer, but also a massive number of peripheral devices, including disks, monitors, keyboards, network connections, cameras and more. Often when a new device is developed, the developers need to provide some way to plumb it through the operating system so that applications will be able to take advantage of it. As we will discuss, device drivers are the vast majority of software in today’s operating system.

2.2.8. Putting it together#

So, to summarize, the operating system is responsible for:

Creating the fundamental virtual abstractions that applications are written to use on top of the primitive abstractions provided by hardware. This enables applications to be written without detailed understanding of the hardware, which in turn enables computer system and device developers to develop new hardware that applications can just use.

Managing and multiplexing the hardware resources to support diverse workloads by many users across a broad set of use cases from supercomputers to cell phones. This includes providing the interfaces and tools that operators use to manage their systems.

Protecting processes/users from both internal and external attacks and keeping activity logs.

In other words, operating systems are the fundamental platforms that all other software and hardware relies on and that people use to interact with the software and hardware.

2.3. So why do we care#

In all fields, if you control the platform that others need to use, you have an enormous advantage. For example, if you control the exchange that others use for trading stocks, cryptocurrency or goods (e.g., Amazon and etsy) you are in a position to (properly or not) gain something from every use of the platform, and you have a special responsibility to all the users. As the fundamental platform in computing, we see that operating systems have played a huge role. For example:

Operating systems have been the focus, and responsible for the success, of some of the world’s largest companies, e.g. Microsoft, VMware, Red Hat.

Operating system people play a key role in every major technology company.

Every major change in technology requires innovation or at least changes at the operating system level.

Operating system researchers, and their venues (e.g., SOSP, OSDI, Eurosys, Usenix) are responsible for the major distributed system innovations.

The world of open source, that has impacted all elements of society, started with operating systems.

Fundamentally, if you care about computing, you better care about operating systems and have some idea of how they work. If you want to develop applications, you need to understand the OS abstractions, and good performance often relies on understanding something about the policies and implementation of the OS you are using. If you want to develop new hardware, you need to understand how to expose that hardware through the OS to the applications that want to use it. If you just want to use computers, you need to understanding the fundamental capabilities and protections that the operating system can provide to secure and manage the hardware.

2.4. Is the fun over?#

We have been working on operating systems for as long as we have had computers. In many fields, innovation happens rapidly for a while, and then the excitement moves to another area. With operating systems, not only do they continue to be a major area of innovation, but we expect that the need for innovation in operating systems, and even development of new ones, will continue and accelerate.

Fundamentally, OS innovation is needed for any major change in application requirements, hardware capabilities, or new use cases. Consider some of the major changes that are happening now:

The rise of cloud computing is resulting in new models of OS for services and functions that require “logical” computers to be instantiated in seconds, and demand strong guarantees on tail latency (i.e., most requests finish in some guaranteed time).

Fundamental change in security requirements; provider/tenant

Denard scaling is over; but network and storage keep getting faster…

Edge computing & Cloudlets driven by the emergence of high bandwidth low latency 5G will drive a whole new model of compute.

While persistent memory has been promised for decades a few years ago the first products became available. (and just got cancelled)

Rise of smart NICs where intelligence is embedded into the devices, enabling new models to offload computation to the network; e.g. high speed trading, security, accounting cloud…

100 GB networks spanning the world..

Rise of AI…

Unfortunately, for some reason many engineers and computer scientists are intimidated to work at the operating system level, and many think of the OS as underlying plumbing with the fun stuff around it. We hope that this chapter has motivated you to understand why operating systems are not only historically interesting, but will continue to be a major area of innovation, and that this this course will start you on the path to mastering this exciting and important topic.